News and Media

NCEO scientists at the University of Leeds contribute to the Global Nitrous Oxide Budget 1980-2020 which exposes alarming measurements

Global emissions of nitrous oxide (N2O), a powerful greenhouse gas, continue to rise unabated, largely driven by unsustainable practices in global food production and growing food demand

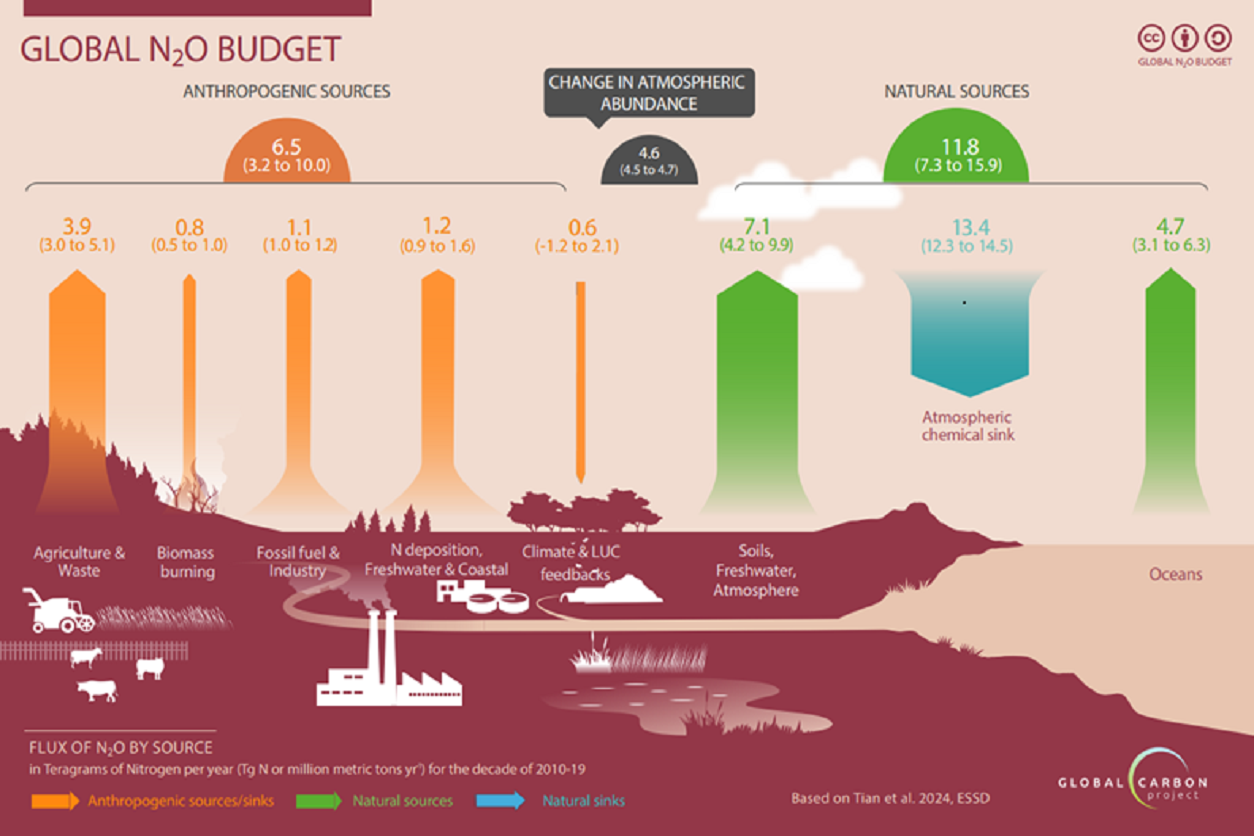

Emissions of nitrous oxide (N2O), a long-lived greenhouse gas more potent than carbon dioxide or methane, have continued to increase unabated up to 2020, a new report by the Global Carbon Project has shown. N2O, which lasts for around 120 years in the atmosphere, is emitted from a range of sources, with agricultural-related emissions – primarily due to widespread use of fertiliser – leading the human-driven contribution.

In an era when greenhouse gas emissions must decline to reduce global warming, in 2020 and 2021 N2O was emitted into the atmosphere at a faster rate than at any other time in history. On Earth, excess nitrogen is particularly damaging to water systems and contributes to soil and air pollution. In the atmosphere, it depletes the ozone layer, and exacerbates climate change.

The report, “Global Nitrous Oxide Budget 1980-2020”, was published today in the journal Earth System Science Data. Led by Hanqin Tian at Boston College Schiller Institute for Integrated Science and Society, it shows that agricultural production accounted for 74 percent of human-driven nitrous oxide emissions in the 2010s. Agricultural emissions reached 8 million metric tons in 2020, a 67 percent increase since 1980.

The unfettered increase in a greenhouse gas with a global warming potential approximately 300 times larger than carbon dioxide, presents dire consequences for the planet. The concentration of atmospheric nitrous oxide reached 336 parts per billion in 2022, a level beyond even the range of predictions previously developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Drawing on millions of nitrous oxide measurements taken during the past four decades on land and in the atmosphere, freshwater systems, and the ocean, Tian said the researchers have generated the most comprehensive assessment of global nitrous oxide to date. The study was produced by a team of 58 researchers from 55 organizations in 15 countries.

The researchers examined data collected around the world for all major economic activities that lead to nitrous oxide emissions and reported on 18 anthropogenic and natural sources and three absorbent “sinks” of global nitrous oxide, according to the report.

The top 10 nitrous oxide emission-producing countries are: China, India, the United States, Brazil, Russia, Pakistan, Australia, Indonesia, Turkey, and Canada, the researchers found.

Some countries have seen success implementing policies and practices to reduce nitrous oxide emissions, according to the report. Emissions in China have slowed since the mid 2010s; as have emissions in Europe during the past few decades.

Dr Chris Wilson, scientist at the National Centre for Earth Observation at the University of Leeds, contributed to the ‘inverse modelling’ section of the study, using measurements of atmospheric N2O and a model of atmospheric transport to estimate emissions of the gas over the past 25 years.

In this study, multiple groups did the same type of inverse modelling, so the results were not dependent on a single model. These ‘top-down’ results were then compared to ‘bottom-up’ estimates from other groups who simulated N2O emissions directly. The two methods produced consistent results.

Dr Chris Wilson, NCEO: “This study highlights the need for more considered use of fertilisers within global agricultural systems, otherwise atmospheric N2O concentrations will continue to rise at alarming rates. There is plenty of evidence that we can maintain or increase crop yields whilst limiting the amount of fertiliser applied, if it is done in a targeted way.”

Established in 2001, The Global Carbon Project analyzes the impact of human activity on greenhouse gas emissions and Earth systems, producing global budgets for the three dominant greenhouse gasses – carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide – that assess emissions and sinks to inform further research, policy, and international action.

“We must reconsider many of our current practices in agriculture with a more rational use of nitrogen fertilizers and animal manure to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and water pollution,” said Global Carbon Project Executive Director Josep Canadell, who is also a research scientist at Australia’s CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research.

While there have been some successful nitrogen reduction initiatives in different regions, the researchers found an acceleration in the rate of nitrous oxide accumulation in the atmosphere in this decade. The growth rates of atmospheric nitrous oxide in 2020 and 2021 were higher than any previous observed year and more than 30 percent higher than the average rate of increase in the previous decade.

Tian said there is a need for more frequent assessments so mitigation efforts can be targeted to high-emission regions and economic activities. An improved inventory of sources and sinks will be required if progress is going to be made toward the objectives of the Paris Agreement.

Journal link: https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-16-2543-2024

Latest News and Events